Molam

“Thai-ppalachian" if you will. Traditional sounds and modern takes on music from the countryside of Southeast Asia.

Check out this week’s playlist HERE. I love the term that Chaco Pastorius coined to describe molam: Thai-ppalachian. It perfectly encapsulates how this genre represents the rural people of Thailand. The music is fast paced, elastic, string heavy, and really fun. I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

Last week we discussed an example of a political movement shaping music. It was a story with colonial uprising, cultural expression, and Cold War tensions… what more could you want? I’m glad that Songs in Situ started with a bang, but how the hell am I supposed to follow that up?

Well - without further ado…. MOLAM!

Molam, or mor lam or mawlum or moh lam or mhor lum or more spellings than you’d believe, is an absolutely electric genre coming out of Isaan, an area in northeastern Thailand and southern Laos. The term comes from the Laotian expression for expert (mor) singer (lam).

As with every one of these articles I should start with a disclaimer: this post is not academic. To quote Arthit Mulsarn, a curator of the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok: "Molam as entertainment and molam in the academic sphere are completely different. Doing researching on molam is extremely difficult." And yeah, I felt that…

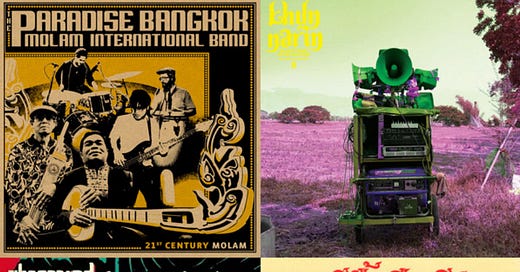

The playlist above began to come together about a year ago when I was pulling at the threads of bands like Khruangbin and Yin Yin. If you’re not intimately familiar with both of those bands, go check them out. I love them and wanted to learn about their inspirations. Queue The Paradise Bangkok Molam International Band (TPBMIB). The influence of this genre on modern groove bands is abundant. Take Khruangbin’s song People Everywhere. A guitar plucks at notes with little discernible pattern, space opens for a drum fill, and the following string heavy melody fuses the two parts with impeccable harmony. Classic TPBMIB, amirite? Oh also khruangbin literally means “airplane” in Thai, so don’t tell me the influence isn’t there.

Ramblings aside, whats the story with Molam? Well, it’s a tale of people overcoming prejudice and standing firm in their cultural identity. Across the majority of history, this genre was almost entirely written off by the urban Thai people as “county bumpkin” music, sounds that belonged in a taxi cab or sequestered to the far reaches of the rural north. From everything I read, acknowledging this disgust for molam seemed to be a requirement for any article on its history… but why?

Why was a music genre decidedly considered to be undesirable by an entire population? That was the question that I set out to answer. I have come up with a few theories, but I never really found a concrete answer. As with most questions in history, I don’t think our answer is one definitive event but instead many many years of insecurity, compiling sentiments, and rising tensions. That said, let’s try to break it down.

The easiest explanation (shoutout Occam) is just a product of classic, old-fashioned, nonsensical racism. Maft Sai, the DJ and club owner responsible for bringing TPBMIB to global acclaim, said “[People from Isaan], their parents listened to this when they were growing up, but they’re ashamed to be part of this music. It relates back to being from Isaan, having darker skin, being working class, being in the rice fields.” There is a very prevalent racial discrimination in Thailand, and distaste for molam is a product of that.

The source of that prejudice is interesting because in the 1850’s molam was proving to have the potential to erode the walls of cultural separation. Per the traditions of Southeast Asian Imperialism, the people of a conquered area were subject to capture and relocation to provide forced labor. This pattern facilitated an influx of Lao speaking people to the growing city centers of Thailand during the 19th century. With the relocation of people comes the assimilation of cultures. The laborers from Isaan played their music and it attracted large crowds. People loved it! But, a handful of people wasn’t enough.

King Mongkut of the Chakri Dynasty of Siam believed that the popularity of an “inferior” ethnic group was causing natural disasters, so in 1857 he outlawed Molam by royal decree making it illegal to play the music. Perhaps it’s a frivolous hypothetical, but what if he hadn’t done that? I’d like to think that we’d be telling a different story of race relations in Thailand today.

There isn’t a lot of literature on the history of molam, and the story doesn’t really pick up again for another 100 years. That’s why I think that King Mongkut’s decree is really important to the story and it likely created a distrust of the music that infects modern sentiments. That’s just a theory, there’s more research to be done.

Now molam’s rise to influencing international bands and boasting record deals is kind of a complicated journey, but in short there were two major waves.

The first wave is a little muddier, but it was a product of Western influence during the 60’s and 70’s. A growing presence of military outposts in Southeast Asia brought a population of American GI’s who were listening to rock and funk and psych and soul. This music fusing with molam just make’s sense. They share string heavy passages, high tempos, and for funk and soul, themes of overcoming social class and adversity. Some of the first ‘molam’ tracks we hear from the 70’s are really just artists from Isaan reimagining western music. Now, here’s where it’s hard to separate the threads. There were also plenty of artists from Bangkok doing the same thing. Artists that would have scoffed at molam. However, they were also new to the electric guitar and held similar approaches to music theory, so deciding what is and isn’t molam from this period is hard for someone who doesn’t speak Thai or Lao.

The second wave of molam on the global stage is largely thanks to a DJ we mentioned earlier, Maft Sai, also known by his given name, Nattapon “Nat” Siangsukon. Maft Sai owns a club in Thailand and more importantly, he owns multiple international record labels. Under these labels, he released two volumes of The Sounds of Siam which published the available recordings of those rock/molam tracks from the 60’s and 70’s. They gained so much support that he facilitated the creation of The Paradise Bangkok Molam International Band. Another modern molam band that falls into this circle is Khun Narin. Their prominence came from a 2011 YouTube clip recorded on an iPhone. Ultimately, the draw to this music is infectious and if you’re listening to this week’s playlist, you know why.

So in 2025, where is molam? Well… it’s all over the world, influencing some of your favorite bands and maybe even making cameos in your favorite TV show. If you’re watching White Lotus Season 3, TPBMIB can be heard across episode one, and I don’t think that will be their last appearance. The prejudice towards people from Isaan is still a thing in Bangkok, but it’s lessening largely in part to molam! People are being brought together by this music once again.

——

Whew, that was journey, huh? If you made it this far I commend you. Research for this article got pretty out of hand, and I feel like the monkey brain is really reflected in my writing. Yet, somehow, I only scratched the surface. In some places, the molam subgenres got mangled together and I didn’t credit the uniqueness of them enough… and in other places I made some assertions that probably don’t have adequate sources. Alas, I did my best.

Thanks as always for sticking around and I’ll see ya next time!

Igula Lendlebe Aligcwali